Earlier this year, the city of Chicago, Illinois, and Green Roofs for Healthy Cities co- hosted the first green roof infrastructure conference and trade show in North America. (At least six green roofs already exist in Chicago, including one covering city hall, and an additional 42 are in the planning stage.) Over 500 architects, landscape architects, roofing contractors, city planners, developers, and others attended the conference to learn and share on the subject, and generate support for green roofs throughout North America.

Increased interest in green roofs

Several U.S. companies are licensees for European green roof systems and methods, where the technology has existed for the past 40 years. In fact, limited land resources (as compared to North America), expensive sources of energy, and ancient sewer systems overwhelmed by storm water runoff have all contributed to the success of the green roof industry in Europe.

Over 800 green roofs can be found in Germany alone, a leader in building codes and incentives for green roof installation. In Asia, Japan has become a center for green roof technology. Its capital, Tokyo, is the first city to mandate building vegetation must constitute 20 percent of all new construction.

Green roofs have been installed across America in steadily increasing numbers over the past decade, and research is being conducted in North American universities on the impact of green roofs on the environment, economy, and energy resources. Some major

American corporations, like Ford Motor Co., The Gap, and H.J. Heinz Co., have recently installed green roofs, and the approved design for the new World Trade Center includes a rooftop garden. However, despite breakthroughs in green roof elements making them more readily available in the United States, little is known about green roofs and even less about their installation standards.

History of green roofs

Green (vegetated) roofs have been in existence since ancient times. “The first known historical references to man made gardens above grade were the ziggurats (stone pyramidal stepped towers) of ancient Mesopotamia, built from the fourth millennium until around 600 B.C.” In France, gardens planted in the 13th Century thrive atop a Benedictine abbey. Norwegians developed sod roofs centuries ago as a means of thermally insulating their buildings. In fact, sod homes are still used as protection against extremely cold winters in Norway and the United States. Five roof gardens were installed atop the seventh floor of the Rockefeller Center in New York City, New York, between 1933 and 1936. Designed to be ‘viewscapes’ for the enjoyment of skyscraper tenants (at higher rents, of course), these gardens continue enhancing the view in New York City.1

Description of systems

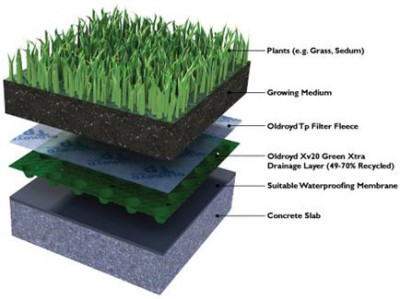

The green roof industry has developed two general classifications for rooftop vegetation systems:

Extensive: Also known as low-profile or performance, this type of green roof contains only one or two plant species and minimal planting medium. It is commonly designed for maximum thermal and hydrological performance and minimum weight load while being aesthetically pleasing. Typically, only maintenance personnel have access to this type of roof. It is installed on flat and pitched roofs.

Intensive

Also known as high-profile or rooftop garden, this type of green roof typically contains a variety of plant types and is designed as a park-like setting (Photo 2). Some rooftop gardens support fairly large trees and water features requiring substantial structural reinforcement. A good example is Central Park atop the parking garage at the Kaiser Center in downtown Oakland, California (Photo 3). It has public access and has been a popular place for lunch since it was built in 1961.

Modular system

In this system, the vegetation and planting medium are contained in special trays covering all or most of the green roof. In a non-modular system, the planting medium is a continuous layer over the entire green roof. The rooftop garden below is a modular system.

All these elements need not be acquired as individual units, as some products and designs on the market combine the functions of two or more components. For instance, the contours of the bottom of a modular container may form a drain layer, or a water storage mat might also be used as a filter layer. Combination designs can often reduce the weight and cost of a system.

Green roof system standards

Green roofs provide exceptional benefits through their thermal, hydrodynamic, and protective characteristics, but the only way their economic impact can be fully appreciated is by allowing variances to established standards and codes for roof systems incorporating vegetation.

Since the individual components of a green roof can be selected or created for a wide range of design possibilities, complying with standards at the component level is a reasonable approach. Exceptions to this would include clarifications in building codes for the total dead-weight (wet and dry) and live loads, fire safety, and provisions for membrane inspection or monitoring. Fire safety is a topic still debated, partly because of misunderstandings regarding the overall construction and type of vegetation used in green roofs. For example, tall grasses are often considered a fire hazard while succulents are fire resistant.Currently, green roof systems are not addressed by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). A Green Roof task group established in October 2001 by ASTM International Subcommittee E06.71 on Sustainability has created a statement of work to explore ways in which to assess green roofs

The other thermal design consideration is leaf retention. Many plants have an additional advantage over cool roofs in that they lose their leaves in the winter, allowing the sun to warm the roof. Selecting plants for maximum thermal benefit is location specific. Buildings, currently allows for reduced insulation in roof systems using a reflective cool roof in warm climates, but it should be expanded to include vegetation in a broader range of climates.

As the production of green roof components increases and improves, and the more they get specified, the more the cost of green roofs and rooftop gardens goes down, resulting in quantity discounts and increased overall savings for the client. Incentives and rebates exist nationwide for cool roofs, yet only a few municipalities have applied those incentives to green roofs.

Portland, Oregon, Chicago, Illinois, and a handful of other cities encourage their installation. A few states, such as Oregon, include green roofs in their environmental and energy savings programs, but it is not enough to encourage the establishment of nationwide standards and consistent codes. Green roofs provide greater energy savings than cools roofs but few areas in the United States provide installation incentives.

The paradox surrounding green roof standards is the lack of official guidelines keeps some specifies from recommending green roofs for their projects, but without a substantial number of projects, there is little need to establish those standards.

Thankfully, with or without standards, green roofs continue to be specified in North America in greater numbers. These developments will assist specifies in making educated, informed decisions and recommendations